Teddy Bear Fetal Development: The Other End of the Cycle

My journey through fake anatomy of made-up creatures began with the skull of a teddy bear, but it veered off into another direction thanks to that familiar combination of curiosity, science, and personal experience. And the result: specimens of fetal development of teddy bears. (At this writing I’ve just created several more, and some are still available in my sculpture shop).

Why, you ask? What could that weird combination have been to lead me to considering how teddy bears might look early in their development?

Well, a trip to the Exploratorium museum in San Francisco in 2007 was the catalyst. I had visited the hands-on educational science museum many times over my life, but you know how sometimes things just jump out at you and have particular new significance? In my wandering through the museum I noticed once again an interactive exhibit about embryonic development about how difficult it is to tell which creature is which when you’re looking at the very early stages of potential life. While I had seen the display before, something was different that time: I was pregnant with a much-hoped-for embryo of my own.

So I had already been thinking about the changing state of a fetus during gestation. And working on unnatural history of teddy bear skeletal anatomy. And it got me thinking: where do teddy bears come from?

(I do actually know they are stitched together in factories or by hand. But we’re extrapolating creatively here, so stop being literal and join me.)

I figured they probably develop along the same lines as other mammals, except that their eyes would obviously be buttons. So I set about making a set of teddy bear fetuses at various stages, out of felted wool of course.

Keep in mind my attraction to the fake science of teddy bears in general is that I see them as a symbol of humans taming nature and making it safe and accessible. Could an actual real, live bear eat or at least maim you without much effort? Yes indeed. Yet many humans grow up thinking of bears as cuddly playthings rather than apex predators thanks to our social conditioning. I think it’s a good idea to acknowledge and respect that wild animals are wild, although I’m not making cheeky art about teddy bears to try to change human behavior. Instead I like to flesh out thought experiments with tangible objects that may cause someone to reconsider everyday things. Like the cute little stuffed representations of awesome (in the original sense of the word) nature that we take for granted.

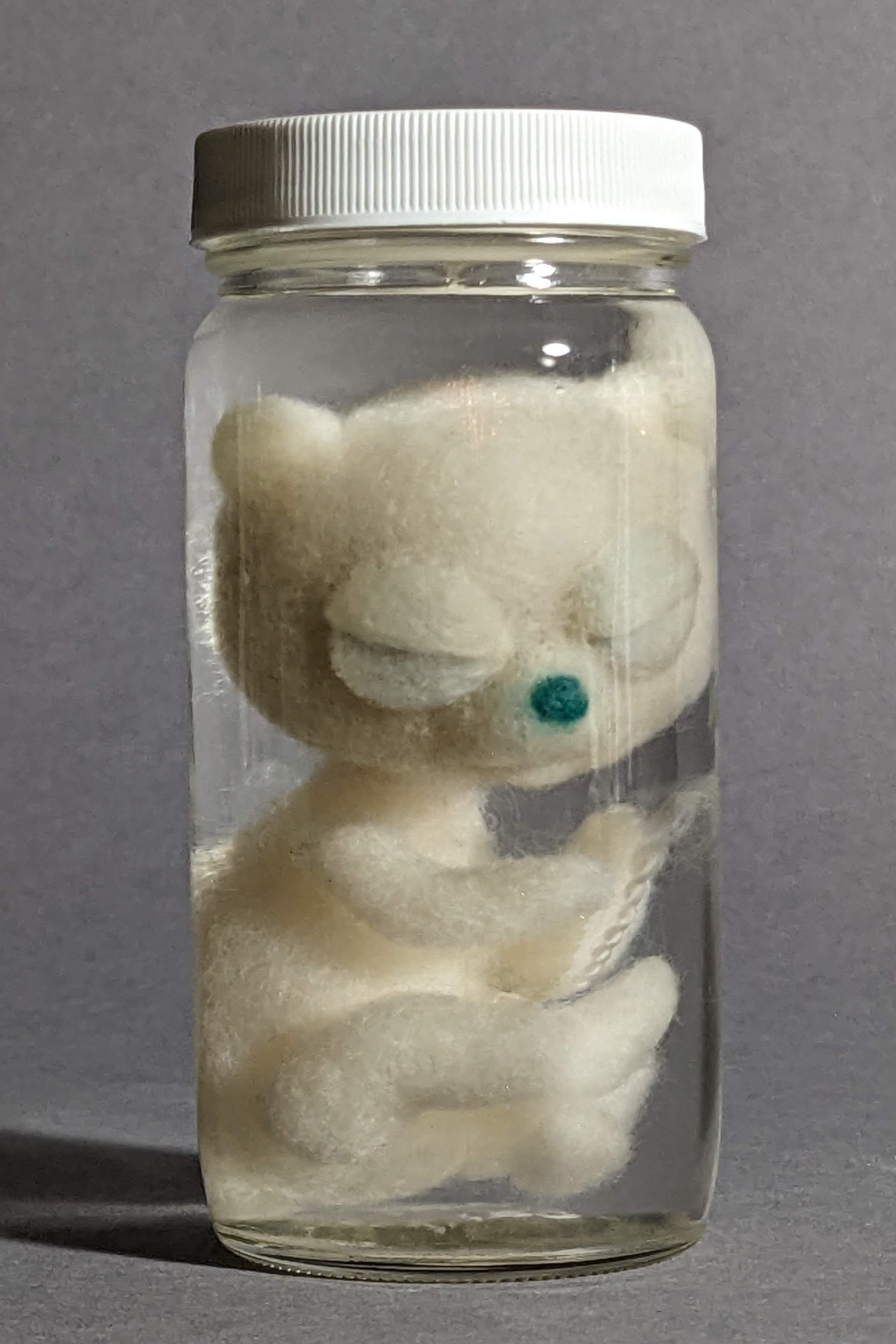

I make teddy bear embryos as objects of awe and wonder. Now, clearly a preserved specimen is by definition not a live specimen, but even from childhood I appreciated that there was a lot to learn about life from studying it after death. So when I’d see jars of pickled biological specimens in the science classroom it was with a sense of wonder and curiosity, but also gratitude to closely study nature in another way. Like skulls, preserved animals make me think not just of what was lost, but of what can be found.

I don’t recall what made me decide to put one in a jar of liquid. It may well have been a visit to another favorite museum, the California Academy of Sciences (also in San Francisco). If you’ve read about the origins of teddy bear skulls you may recall that venue as the source for all of this in the first place. Besides skeletons and fossils, they also boast an impressive collection of specimens that are quite accessible to visitors.

In any case, the moment I submerged a felted wool teddy bear embryo in liquid I was entranced. The liquid served to magnify the sculpture and give it some translucence, letting the button eyes show through the eyelids and causing the tiny fibers to float and wave around with movement of the jar.

It looked both vulnerable and… protected. Cherished. Like a memory frozen in a tangible medium. Like potential, hopes, and dreams— bottled and preserved.

I loved it, and so I made more.

I varied the body shapes, the poses, the size, the eye and nose colors.

Sometimes I even added an umbilical cord, contra-twisting wool fibers like yarn to get the look I wanted.

I learned a lot. For example, an early piece that I’d submerged in distilled water came back from an exhibition with a distinct pink hue and extra fuzzy look. It turns out that there are a lot of things that could be living on wool fibers and thrive in water. I cleaned that specimen and instead tried using ethyl alcohol as a preservative— which worked well but was expensive and difficult to find.

Shortly thereafter I was ready to send a commissioned piece out of state and I discovered that I could not find a legal and safe way to ship ethyl alcohol in a jar due to its hazardous flammability. I turned once again to the CalAcademy to see what they could tell me about transporting wet specimens. I corresponded with the collections manager for Ichthyology, David Catania, who informed me that even major museums don’t ship their wet specimens in alcohol-filled glassware—instead they wrap the specimens in alcohol-soaked cheesecloth inside ziploc bags, and the receiving venue places them in alcohol-filled jars again upon arrival. He also told me I could simply use rubbing (isopropyl) alcohol from the drugstore as a preservative.

I use isopropyl alcohol in my wet specimens to this day— and for shipping the work, I drain out the liquid and order a bottle of alcohol to be shipped directly from a drugstore to the recipient. Problem solved!

Another thing I learned was how to better light and photograph objects floating in glass jars. It took a lot of trial and error and ultimately shrouding the photography area in dark cloth to minimize reflections.

Now, I’m aware that some readers may have gotten this far and feel a little… unsettled by this whole thing. Maybe you think I haven’t addressed the ‘dead baby bear’ angle— that this just seems too dark or flippant and perhaps it’s a comment on when life begins or doesn’t and what should or should not be done or not done about that.

None of that is what this is about for me. It’s the nature of my brain and my personality and my artwork to see and present the ambiguous nature of things— to leave questions unanswered, open-ended, and free for you, the viewer, to interpret how you will. Like everything in life, you see this through your own lens of life experiences.

As to my own life experiences, back when I made the first teddy fetal development series I had already suffered a miscarriage in my journey to parenthood- a fairly common occurrence that doesn’t feel at all common when it happens to you. In the aftermath I was trying to make sense of why biological processes sometimes go awry, aren’t viable, don’t work. I was pregnant again and full of hope and worry and the knowledge that we don’t get any guarantees. Yet my teddy fetal specimen pieces were made of that hope, along with humor and curiosity.

After all, there really are no guarantees. Even now, with two teenagers, I still feel highly aware of that. Got through two healthy pregnancies, first steps, the terrible twos, first days of school, lost teeth, a trip to the ER that could have gone worse— and driving is yet to come. What could we arm ourselves with as humans better than hope, humor, and curiosity?

That’s what these weird teddy fetal specimens are all about. That’s my angle.